Why the differences in Malaysia’s FDI numbers compared with UNCTAD’s?

14 Dec 2023

In the business world, one often makes jokes about mathematics; the famous one is perhaps when a job interviewee is asked what does one and one add up to, to which he replies, “What would you like it to be?” with a conspiratorial wink. Although the joke often alludes to working for the corrupt, the matter itself sometimes comes across in different fields that one plus one does not equal two. More times than not, that happens when something that should be exactly alike, when it is counted by two different organisations, it is, well, not.

Let’s take an example. Malaysia is so very reliant on foreign direct investments (FDI) and its impact on the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) is undeniable. Indeed, through time, it appears as if the entire country must bend over backwards to accommodate FDIs, even to the point of “importing” millions of foreign workers when tens of thousands of local workers, graduates even, are unemployed.

In researching several papers that we have written about industrialisation, trade, labour and associated topics, we came across such a discrepancy, and are at a loss to explain it. One believes that it boils down to minutiae, about how the subject is counted, compared with how it is done by another party. Certainly, one on this side does not equal one on the other side, even though they are supposed to be the exact same thing. There are international standards on how to count this, and that.

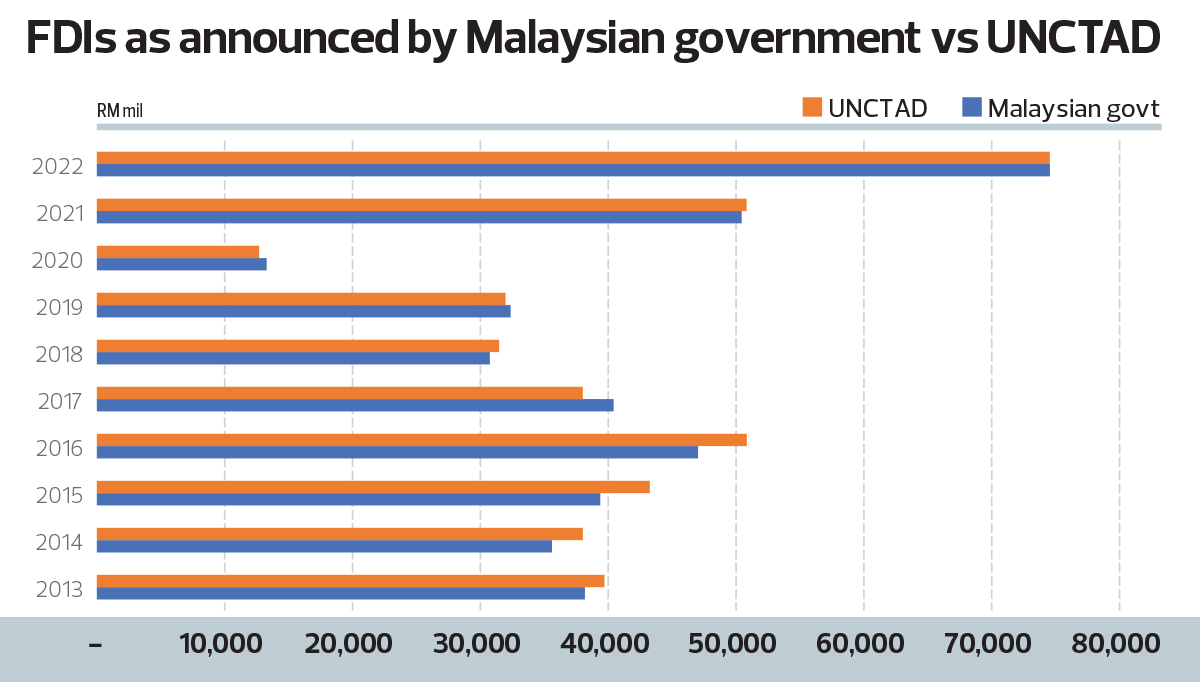

The item that we are talking about is the FDI numbers that have been announced by both the Malaysian government and United Nations Conference on Trade And Development (UNCTAD). There are discrepancies as per below:

The differences in the earlier years are significant, between 3% plus to around 9% between 2013 and 2017. Remember that we are talking about millions of ringgit each year, so, a 1% difference can have some large numbers of currency attached to it. The numbers only seem to converge in 2022, with a tiny 0.2% difference in favour of Malaysia.

Other ramifications immediately pop up. One is, who is over-declaring or who is under-declaring? Why the difference in counting? When I was a student in the US, everyone used a Hewlett-Packard calculator in finance; the stares of disapproval one got when one showed a Japanese calculator were enough to make you fear for your position. Any answer given by that person was immediately discarded as being “inaccurate”. That, however, cannot be the reason here; it most likely boils down to methodology. The rub is that Malaysia’s numbers are consistently lower compared with UNCTAD’s; given the impact that FDI has on Malaysia’s economy, one has to wonder if the GDP numbers themselves are understated.

Needless to say, that has ramifications for public policy decisions.

That hit on confidence is not something the country needs, as the first victim of a lack of confidence is the currency, the ringgit. Many expert comments have been emerging that Malaysia’s economic strategy, relying on exports (from which FDI feeds into), is inferior to Indonesia’s, which is domestic demand-driven and fed by their own manufactured brands and goods. Indonesia is widely expected to be Asean’s giant in a few years.

Thus, without doubt, there should be an audit of these numbers as compiled by the Ministry of Investment, Trade And Industry towards international standards. (Surprised it is not compiled by the Department of Statistics, Malaysia? So were we.) To do otherwise, to bring international standards towards Malaysia’s is so unthinkable that it would invite ridicule to even try.

Huzaime Hamid is chairman and CEO of Ingenium Advisors, Malaysia’s financial macroeconomics advisory

Source: The Edge Malaysia