Malaysian ‘Silicon Valley’ seeds homegrown chip startups

12 Apr 2024

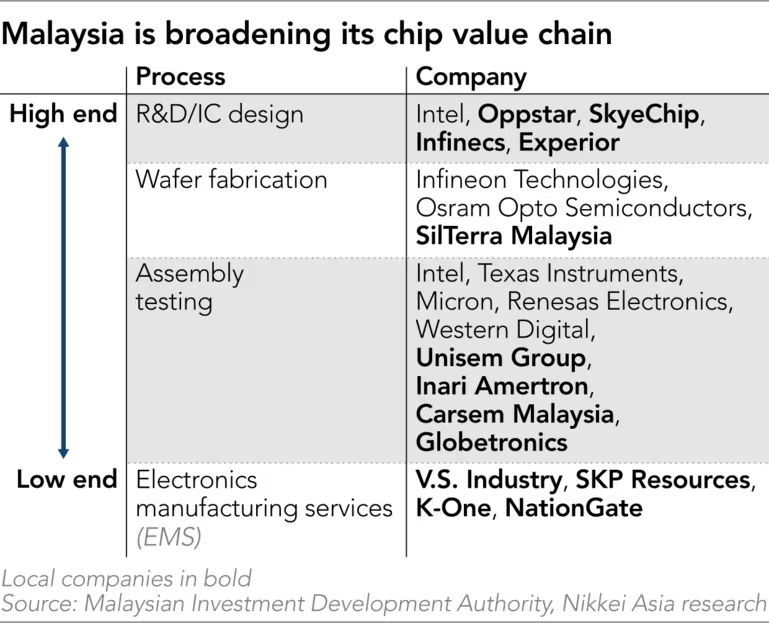

Former Intel engineers attempt to push Penang to higher end of value chain

When chip design company Oppstar listed on the Malaysian stock exchange last year, it was a watershed moment for the Southeast Asian country and its ambitions to revitalize its semiconductor industry.

Amid globally weak public listing activity, investors flocked to the initial public offering, the first by a chip design house on the local bourse. It was oversubscribed by 77 times, pushing its stock price up 286% on its first trading day.

“Being the first one is always tough,” founder and co-CEO Ng Meng Thai told Nikkei Asia. “When we started the IPO process, we feared that many local investors might not know our industry well. So it took us an effort to go and explain.”

Since then, executives from leading American, Japanese and European chip firms have been regular visitors to the company’s office in Malaysia’s northern state of Penang, where its staff of 280 design chips to clients’ specifications.

“It’s been quite a change from the early days, when we were knocking door to door,” said Ng, a 59-year-old former Intel designer. “We were the very few that went against all odds.”

But the fact that Oppstar is the only chip design company listed on the Kuala Lumpur stock exchange is also a sign of how far the country — once known as the ‘Silicon Valley of the East’ — still has to go if it is to return to its former tech glory.

“We would need more Malaysian front-end companies to excel and have an increased significant presence on the international stage in order to lift the country’s profile within the front-end markets,” said Steven Chan, senior equity analyst at Malaysia’s Affin Hwang Investment Bank.

The state of Penang has been known for decades as a cluster for back-end chipmaking processes, including packaging, assembly and testing, which are less advanced than wafer fabrication and other so-called front-end processes.

Startups like Oppstar are looking to change that by breaking out of the back-end and into areas like chip design.

Malaysian Trade Minister Zafrul Aziz says the government seeks to foster such activities. “Nurturing a vibrant startup culture is crucial,” he told Nikkei Asia.

Founded in 2014, Oppstar designs transistor models used for chips from the 20-nanometer level and below, all the way to the most advanced 3-nanometer chips.

“We can work with almost anyone from different industries,” said co-CEO Cheah Hun Wah, who was Ng’s former colleague at Intel.

Unlike the global chip giants Intel and Nvidia, which mainly design and sell their own branded chips, Oppstar is a contract designer, developing bespoke chips for clients. These designs are then manufactured by dedicated makers known as chip foundries.

Oppstar says its experience with various foundries, which all have their own complex set of rules, has allowed it to secure projects from global clients as supply chains shift in response to geopolitical tensions.

Malaysia has emerged, or rather re-emerged, as a major destination for chip investment as companies like Intel and Infineon Technologies seek to diversify their production footprints. Since Intel opened its first overseas assembly plant in Penang in 1972, the country has played an important role in the global chip industry. Today it is the world’s sixth-largest semiconductor exporter, and the largest contributor to U.S. semiconductor imports, at over 20% by value annually, more than Taiwan, South Korea and Japan.

But despite its long history in the industry, Malaysia was eclipsed by South Korea and Taiwan in the more technologically advanced areas of chip manufacturing — it has not produced its own version of Samsung Electronics or Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. — while the U.S. is the dominant player in chip design.

Failing to get into the front-end is a missed opportunity for Malaysia. Almost 90% of the world’s total semiconductor equipment spending is for wafer fabrication processes, according to industry association SEMI.

“Tapping into that [front-end] market would be crucial in fueling the next stage of [Malaysia’s] semiconductor growth,” said Chan of Affin Hwang Investment Bank.

But fabrication plants are massively expensive — a cutting-edge chip plant built by TSMC or Samsung can cost billions of dollars.

With this level of spending beyond most local companies, Wong Siew Hai, president of Malaysia Semiconductor Industry Association, sees the more asset-light chip design business as a “key area” for newer entrants. “There are now many [venture capital] funds focusing on Malaysia,” Wong said, “and we encourage such talents to seek them for support.”

Fong Swee Kiang, another Intel veteran, shares Wong’s view.

Fong founded semiconductor design house SkyeChip in 2019, shortly after leaving chip developer Broadcom. In charge of global operations at the American company, he was on the frontline as the U.S.-China chip war broke out in 2018.

“There were restrictions on selling to certain customers. We started to feel the force of deglobalization,” Fong recalled of the U.S. export controls first imposed under the Trump administration. But this had a silver lining, he said, as it created more markets and lowered the entry barrier for smaller chip designers. “In the old days, there was one single market [the U.S.] with a lot of giant players.”

As the first local Intel engineer sent to the U.S. for training, Fong was responsible for setting up the company’s design center in Penang, which eventually grew to 1,500 people.

Today, SkyeChip designs AI chips for data centers, automotive and connected devices and boasts a dozen or so of its own patents on next-generation chips and other technologies, according to Fong.

In Asia, the contract chip design sector is crowded with companies like Taiwan’s Faraday Technology, Global Unichip, Alchip Technologies and Japan’s Socionext. While the global on-shoring of semiconductor production, as Fong pointed out, opens up more opportunities for challengers like SkyeChip and Oppstar, industry players say the trend is also exacerbating the long-standing problem of a shortage of qualified chip engineers.

Attracting engineers is a particular problem for Malaysia because of the strong presence of large multinationals offering higher salaries than local companies. Many locals also choose to work in neighboring Singapore, another semiconductor cluster.

“One of the key areas we need to look into is how to grow talent within [Malaysia] and to attract talents from abroad,” said Kalai Selvan Subramaniam, a former Intel designer and CEO of Malaysian chip design firm Infinecs Systems.

Attracting and retaining talent is not the only challenge to growing Malaysia’s chip industry. Investment is booming in Penang, but the cluster still relies heavily on foreign multinationals. The state attracted 60.1 billion ringgit ($12.65 billion) in foreign direct investment in 2023, according to government data, while domestic investment has hovered at around 3 billion ringgit over the years, significantly smaller than the FDI levels.

“FDI is a good thing, but it also has some downsides,” said Experior CEO Eugene Khoo, another former Intel colleague of Oppstar and SkyeChip founders. “It kind of pigeonholed us in the luxury boxes.” Experior tests and verifies new designs before they are put into mass production to ensure the manufacturing process goes smoothly. The company also provides training for universities and companies to help expand the local talent pool.

Developing a more advanced chip industry with a more skilled workforce is critical for Malaysia as other Asian countries with cheaper labor, like Vietnam, Thailand and India are also competing to build up semiconductor sectors. To that end, local officials and industry players say relying on FDI will not be enough.

Loo Lee Lian, CEO of InvestPenang, the non-profit arm of the state government, stressed that FDI is “only one of our areas of focus,” and that the state pushes foreign firms to localize their supply chain, or set up joint ventures as part of the criteria for approving projects.

“To fulfill our aspiration to move out from the middle income trap … we have to move up the value chain,” Loo said. “We cannot be competitive for commoditized products, or products that are too cheap.”

Source: Nikkei Asia