Chipping in to move up the E&E value chain

20 May 2024

AS Malaysia finalises its Semiconductor Strategic Plan (SSP), expectations are high for a roadmap that will not only attract global players but also elevate local firms in the electrical and electronics (E&E) sector.

The Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry (Miti) is set to unveil the comprehensive strategic plan for the country’s semiconductor industry by as early as the end of this month.

Stakeholders, investment promotion agencies and industry players are eagerly anticipating measures that will ensure Malaysia’s ascension up the E&E value chain, a goal that has been discussed for the past five years, but tangible steps have yet to be taken.

This strategic initiative comes at a crucial juncture as Malaysia seeks to capitalise on its competitive advantage amid the ongoing US-China chip war and trade diversion.

Being the world’s sixth largest exporter of electronics and semiconductors, Malaysia plays a critical role in the global E&E supply chain. For perspective, the country is responsible for 7% of semiconductor trade flows, as well as 13% of back-end operations globally, including chip testing and packaging.

Notably, Minister of Investment, Trade and Industry Tengku Datuk Seri Zafrul Abdul Aziz reportedly said last month: “The semiconductor sector is critical to the country’s economy. Given our market share in the semiconductor industry, we need to have a concrete and strategic plan. The timeline given to us is until the end of May.”

Earlier in April, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim said the National Investment Council, which he chairs, had decided that Miti would draw up a comprehensive SSP to attract foreign semiconductor companies to establish high-quality chip manufacturing facilities in Malaysia.

So, what are the key demands and aspirations of players in the E&E and semiconductor industries? Do they expect the upcoming SSP to prioritise the growth of local firms or focus on attracting foreign players? More importantly, what are the main strategies and areas of focus envisioned in the plan, and will there be any new incentives?

When contacted by The Edge, Miti declined comment, saying that the ministry was “in the final stages” of preparing the SSP.

Malaysia Semiconductor Industry Association (MSIA) president Datuk Seri Wong Siew Hai points out that the country already has its E&E aspirations laid out in the 12th Malaysia Plan (12MP), National Investment Aspirations (NIA) and New Industrial Master Plan (NIMP) 2030.

However, the semiconductor landscape is experiencing “rapid tectonic shifts” with developments in technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), as well as the Fourth Industrial Revolution (IR4.0), environmental, social and governance (ESG) compliance and geopolitical tensions between the US and China. Therefore, Malaysia needs to regularly review and update its plans to meet the challenges facing the country’s E&E industry, including talent development.

“The SSP should have an overarching ambition and vision for Malaysia that is holistic, comprehensive [one that includes all the enablers], have specific focus areas and detailed action plans, with owners and timelines,” Wong tells The Edge.

“The SSP should be regularly reviewed for performance and updated to reflect the current environment. As the global competition for semiconductors is intense, Malaysia needs to constantly improve the ease of doing business, develop more talent and be globally competitive.”

Over the years, local semiconductor and semiconductor-related firms, especially the public-listed ones, have been mostly involved in the mid- to lower-end of the value chain, serving foreign semiconductor manufacturers, brand owners, integrated circuit (IC) developers and fabricators.

The first group comprises outsourced semiconductor assembly and test (OSAT) companies such as Inari Amertron Bhd (KL:INARI), Malaysian Pacific Industries Bhd (KL:MPI), Unisem (M) Bhd (KL:UNISEM), Globetronics Technology Bhd (KL:GTRONIC) and KESM Industries Bhd (KL:KESM).

The second group consists of automated test equipment (ATE) firms such as ViTrox Corp Bhd (KL:VITROX), Pentamaster Corp Bhd (KL:PENTA), Mi Technovation Bhd (KL:MI), QES Group Bhd (KL:QES), TT Vision Holdings Bhd (KL:TTVHB), Aemulus Holdings Bhd (KL:AEMULUS), Elsoft Research Bhd (KL:ELSOFT), MMS Ventures Bhd (KL:MMSV) and VisDynamics Holdings Bhd (KL:VIS).

Then there are the likes of JF Technology Bhd (KL:JFTECH), FoundPac Group Bhd (KL:FPGROUP), UWC Bhd (KL:UWC) and SFP Tech Holdings Bhd (KL:SFPTECH). These are engineering firms that produce precision parts, components and other important materials for semiconductor manufacturing and testing activities.

However, there aren’t too many players at the front end of the semiconductor manufacturing process that are focusing on IC design.

Wong says one of the biggest expectations is for the SSP to make the E&E industry and its ecosystem relevant and competitive.

“With over 50 years of experience, Malaysia has made significant improvements to strengthen its supply chain. However, it needs to continue striving to not only keep up with technology but also to broaden and deepen its semiconductor ecosystem and continue to invest and innovate up the value chain,” he adds.

Officially registered in January 2021, MSIA is an association of individuals and companies incorporated in Malaysia that are involved directly or related to the semiconductor industry and its supply chain.

Small window of opportunity

From its origins as a labour-intensive and low-value-added industry, Penang’s E&E sector has evolved into a capital-intensive, knowledge-based and high-technology hub. Today, the state has earned the moniker “Silicon Valley of the East” for its robust E&E ecosystem.

This transformation began in the 1970s when eight major players known as “The Eight Samurai” — Intel, Robert Bosch, Clarion, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), Hewlett-Packard (now Keysight Technologies and Agilent Technologies), Litronix (now Osram Opto Semiconductors), Hitachi (now Renesas Electronics) and National Semiconductor — established operations in Penang. While National Semiconductor is no longer operating in Penang after its acquisition by Texas Instruments, the legacy of these pioneering companies laid the foundation for Penang’s reputation as a global E&E powerhouse.

Despite the state’s long-standing reputation as an established E&E hub, there had not been a national semiconductor roadmap until recently. So, why is there a pressing need for a comprehensive strategic plan now?

Invest-in-Penang Bhd (InvestPenang) CEO Datuk Loo Lee Lian opines that the geopolitical competition between the US and China has given Malaysia a “once-in-a-generation opportunity” to reorganise the country’s place in the global supply chain.

“With intense competition for FDI (foreign direct investment) from other Asean countries and India’s ambitions for the industry, the comprehensive strategic plan is urgently required to streamline our resources, formulate our strategies and identify which part of the value chain Malaysia should focus on and strengthen. We have only a five-to-eight-year window to capture this opportunity,” she tells The Edge.

For that, InvestPenang suggests that the strategic plan for the semiconductor industry enhances the resilience and stickiness of Malaysia’s E&E supply chain and incentivises gaps. The SSP should also focus on high-quality projects, selected based on its strategic contribution, technology sustainability and skill transfer to preserve and prevent resource exhaustion.

“We need to identify and strengthen each state’s competitive advantages to compete on the global front instead of internally. Besides, the plan should empower our local companies to expand into the global value chain,” she says.

Loo also says the success of NIMP 2030 depends largely on the availability of talent and the readiness of the workforce in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). “A national talent blueprint is needed to address human capital strategies and build a sustainable STEM workforce.”

InvestPenang is the principal investment promotion agency of the state government.

BlueChip VC Sdn Bhd co-founder Datuk Lai Pin Yong concurs that there is a “heightened sense of urgency” for Malaysia to capitalise on its competitive advantage.

“Given global trends and the US-China chip war, there is an urgent need for comprehensive strategic planning and swift execution as the window of opportunity is less than five years. Building consensus among government, industry and the public is essential, with a focus on educating young people on high-tech careers and fostering closer public-private partnerships,” he says.

To capitalise on the window of opportunity created by external factors such as the US-China trade tensions and growing chip demand, Lai says it is essential for Malaysia to come out with a systematic implementation plan driven by political will.

“Emphasis on STEM education, from schools to institutions of higher education, alongside broader societal support, is crucial. Malaysia should aim to establish itself as a key semiconductor hub, mitigating global risks by diversifying chip production away from regions prone to instability,” he adds.

“Increased offerings of semiconductor-related courses at institutions of higher education and technical colleges, alongside greater intakes of engineering students, are crucial.”

George Town-headquartered BlueChip VC started out as a specialised technology fund in early 2023. Its main objective is to nurture Penang-based semiconductor companies in three promising segments — advanced packaging, IC design and niche equipment — and eventually have them listed on Bursa Malaysia.

Lai, a semiconductor veteran turned venture capitalist, was among the pioneer batch of Malaysian engineers when Intel set up shop in Penang in 1972 — the US chip giant’s first overseas manufacturing facility.

According to him, Penang’s semiconductor industry, while successful, faces constraints such as land scarcity, water shortages, congestion and a lack of engineers. To address these challenges, strategic planning should focus on complementary development across Malaysia.

“Penang could transition mature manufacturing processes to other regions while upgrading to higher-value activities. A national semiconductor corridor along the west coast could distribute semiconductor activities across various states, reducing congestion in Penang,” says Lai.

Expanding beyond Penang

Interestingly, the Selangor government, through its digital economy arm Selangor Information Technology and Digital Economy Corporation (Sidec), is leading the establishment of an IC design hub in Puchong, touted to be the largest in Southeast Asia. The project — in collaboration with the federal government, international semiconductor firms and venture capitalists — is said to be a strategic move to position Malaysia as a potential powerhouse in the global IC design industry.

The proposed IC Design Park, poised to begin operations by July 2024, has already secured the commitment of four partner companies — ARM Ltd, Phison Malaysia, SkyeChip Sdn Bhd and Shenzhen Semiconductor Industry Association.

To comply with the evolving green standards and ensure long-term growth, Sidec CEO Yong Kai Ping says Malaysia could leverage a multi-pronged approach.

“Instead of internal competition, we can seek partnerships and resource diversification across the region, collaborating with advanced industrial states like Penang, Selangor and Johor to ease the burden on specific areas in Malaysia. This would allow local companies to flourish and participate in the global value chain,” he points out.

Yong goes on to say that Malaysia’s existing specialisation is a strength and the synergies to be derived between the states could foster a robust E&E ecosystem. For instance, Penang and Kulim excel in back-end testing, packing and fabrication, while Selangor focuses on front-end fabless IC design.

“While we focus on internal competition topics, we may overlook external competitors like Saigon High Tech Park in Vietnam that present a significant challenge. This 700ha park houses the entire IC design, fabrication, testing and packaging supply chain under one roof,” he says.

“Additionally, Vietnam is actively investing in talent development through collaborations with universities, building testing labs and training programmes [in South Korea] to increase their pool of IC designers [currently at 3,000].”

Therefore, says Yong, Malaysia needs to rival and do better than Saigon High Tech Park, which could develop to be as capable as the tech parks of Penang, Kedah and Selangor combined, looking at its current rate of development.

MSIA’s Wong says the SSP should provide Malaysia a clear focus and path forward to achieve its aspirations, so states in the country should not view each other as competitors.

“We should complement each other and enable those states with such goals to flourish. Other states [outside Penang] will provide choices to investors, both local and foreign,” he adds.

“It is important that we focus on global competition as it is intense and every other country wishes to have a piece of the semiconductor pie. We need to constantly keep up with technology and improve in every aspect of doing business to ensure Malaysia is a choice location for investments.”

Given the ongoing geopolitical tensions, Wong says the competition for semiconductor supremacy is “a continuous race with no finishing line”.

“There must be no complacency and we need to have a good plan that keeps all stakeholders humble and accountable. We need the whole country to support and nurture the semiconductor and E&E industry to become the ‘Golden Goose of Malaysia’,” he adds.

On industrial park development, BlueChip VC’s Lai says joint ventures between the government and private sector to develop integrated smart industrial parks can support advanced manufacturing. “Speculative land activities in industrial areas should be discouraged to maintain affordability and attract investors,” he notes.

FDI and DDI equally important

MSIA’s Wong is of the view that the country’s E&E industry needs both FDI and domestic direct investment (DDI) to thrive.

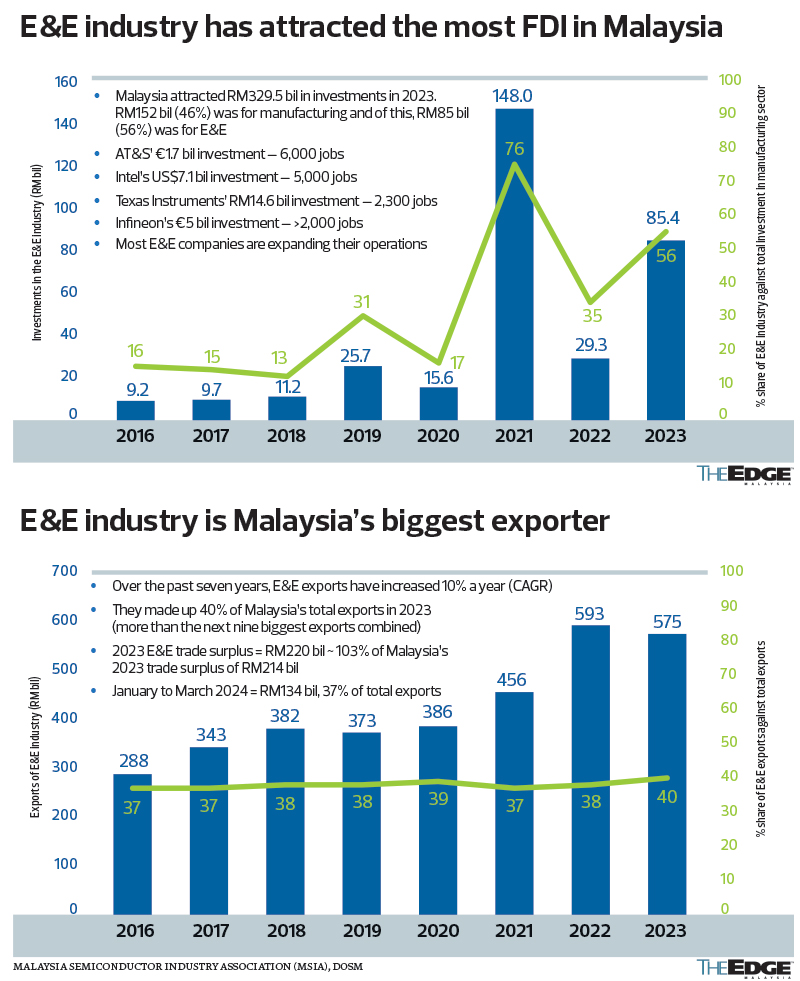

For the past three years from 2021 to 2023, the E&E industry in Malaysia recorded RM262.7 billion of investments. The bulk of these were FDI (97.6%) and only 2.4% were DDI.

“Clearly, Malaysian players are not investing sufficiently in technology, R&D and facilities. Most of the time, these FDI bring with them the latest technology to be deployed in Malaysia,” he points out.

“Malaysian companies need to invest and keep up with technological developments and seize the opportunity to develop new products, equipment and services to support the growth path of these multinational corporations (MNCs).”

Wong says developing Malaysian companies to become global champions and encouraging more entrepreneurs to enter the E&E industry should be one of the priorities of the SSP.

BlueChip VC’s Lai reiterates that the imperative for Malaysia’s E&E industry is to ascend the value chain in tech content and output. Thus, the aim of the strategic roadmap for the Malaysian semiconductor industry is to elevate both technology and value. This plan should entail introducing higher technology throughout the industry, particularly in semiconductor IC design, advanced packaging and equipment.

“As MNCs expand and enhance their technological capabilities, they require a highly skilled workforce, especially engineers and technicians. Incentivising the migration of high-tech jobs from foreign-invested companies to local firms, investing in R&D and IP (intellectual property) development, and attracting skilled talent to Malaysia are key components of this strategy,” he says.

Departing from conventional incentives, Lai believes Malaysia should offer incentives tailored to technology transfer and R&D investment, regardless of whether the companies are domestic or foreign.

“Key performance indicator-driven incentives, such as subsidies, grants, low-interest loans and tax incentives, should be designed to promote specific outcomes. Furthermore, R&D should encompass the development of highly skilled personnel, including support for advanced education. An open policy to attract skilled professionals globally is crucial, with incentives focused on achieving specific KPIs rather than broad tax holidays,” he proposes.

Sidec’s Yong says the semiconductor industry currently faces two major pain points: significant upfront technology investments and securing a steady stream of skilled talent. As a result, a lot of resources and incentives need to be invested to overcome these hurdles.

By taking a leaf from the European Union’s €1.8 billion Chip Fund for Pilots Initiative, Malaysia could establish a dedicated programme to bridge the gap between concept and production for local semiconductor start-ups and small and medium enterprises.

“This programme could offer early-stage funding that provides crucial financial resources for promising projects, reducing the barriers to entry for local talent. It could also offer technical support that provides access to technology and expertise, accelerating the development and commercialisation of innovative ideas,” he says.

The highly anticipated SSP is expected to mark a pivotal moment in the nation’s journey towards moving up the E&E value chain. As the E&E landscape expands beyond Penang to other states in Malaysia, all eyes are on Miti’s comprehensive strategic plan to propel the country towards a more robust and diversified semiconductor industry in the years to come.

Source: The Edge Malaysia