Malaysia’s semicon sector needs to walk a fine line under ‘Trump 2.0’

06 Jan 2025

AS an important link in the global semiconductor supply chain, Malaysia has largely benefited over the past eight years from its neutral stance in the US-China trade war.

However, with tensions escalating under Donald Trump’s second term as US president, concerns are growing over Malaysia’s chip future as new challenges may include the potential of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) nations being the target of US tariffs.

As recently as late November, Trump had threatened to impose 100% tariffs on BRICS nations if they were to create a rival currency to the US dollar. For the first time in many years, industry players are genuinely worried that Malaysia could be caught in the crossfire.

Already, the US Commerce Department has imposed high anti-dumping duties of up to 271.2% on solar products from Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia following complaints from American manufacturers that big Chinese solar panel makers with operations in these countries were flooding the US market with unfairly cheap goods.

Will Malaysia’s semiconductor industry be subjected to similar trade measures?

Adding another layer of complexity, Malaysia is now a BRICS partner country, having joined the bloc in October. A partner country is basically an observer state that receives support from BRICS members, even though it has not yet been officially accepted as a member.

BRICS, originally comprising Brazil, Russia, India and China, was established in 2009 as a cooperation platform for emerging economies, with South Africa joining a year later. Chaired by Russia this year, the trade bloc now collectively accounts for one-fifth of global trade.

For perspective, Malaysia’s semiconductor sector plays a critical role in the global chip supply chain as the world’s sixth largest semiconductor exporter, contributing around 13% to the global chip testing and packaging industry. Globally, about 6% to 7% of semiconductor trade flows through Malaysia.

Malaysia’s strong presence and active participation in the supply chain have historically enabled the country to thrive and strengthen its position, particularly in the wake of the “great decoupling” between the US and China in the tech cold war.

Tariff dispute remains a concern

Will Malaysia’s decision to join BRICS impact its economic ties with the US and its role in the global supply chain? Can Malaysia continue to benefit from the trade war, or is this advantage fading as global trade shifts further?

Pentamaster Corp Bhd co-founder and executive chairman Chuah Choon Bin acknowledges that Malaysia’s economic ties, particularly with China, could expose it to indirect risks from tariffs or trade restrictions, even though it is not a BRICS member.

However, adopting a clear economic strategy — such as advancing the digital economy to promote e-commerce and tech-driven industries, implementing attractive investment policies, fostering global integration and trade, as well as maintaining a neutral diplomatic stance — may help mitigate these risks.

“The possibility of being involved in tariff disputes, particularly within the semiconductor industry, remains a concern if Malaysia continues to play a role as an OSAT (outsourced semiconductor assembly and test) country,” he tells The Edge.

While Chuah expects the country’s semiconductor industry to remain stable in the near future, he warns that the sector could face challenges if technology trade tensions escalate with further heightening of trade sanction policy during Trump’s second term.

Malaysia approved RM254.7 billion in investments during the first nine months of 2024 (9M2024), reflecting a solid 10.7% growth year on year, compared with RM230.2 billion in the same period a year before.

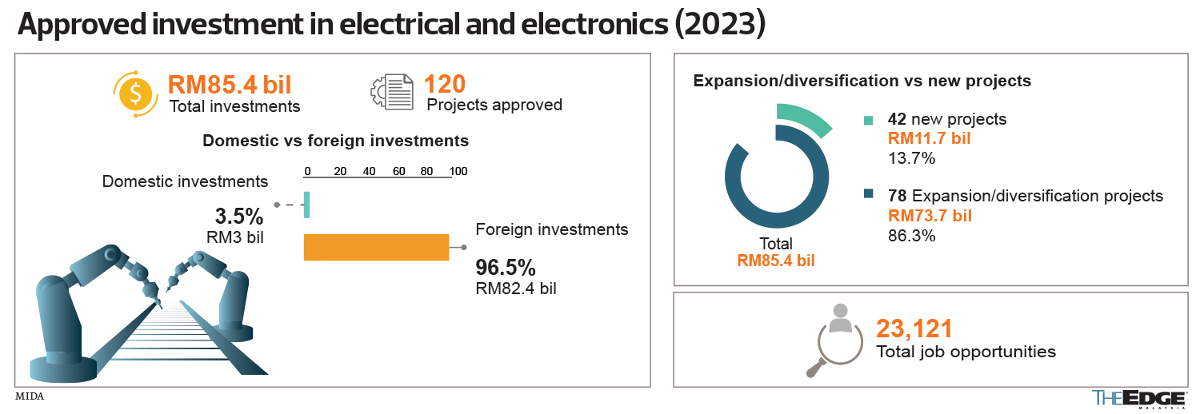

The electrical and electronics (E&E) sector maintained its dominant position as the country’s top manufacturing sector, attracting RM47 billion in approved investments in 9M2024, although it was 18% lower than RM57.3 billion in the same period a year ago.

The semiconductor subsector accounted for over 90% of the E&E investments in 9M2024, demonstrating its pivotal role in advancing the National Semiconductor Strategy towards its RM500 billion target in investments for the sector.

The key priority for Malaysia, says Chuah, is to develop strong foundations in technology and intellectual property (IP), particularly in research and development, such as having our country’s own integrated circuit (IC) design for advanced devices and advanced technology equipment.

“This will help mitigate the impact of trade restrictions, as the global demand for high-tech components and devices continues to grow. By shifting focus towards high-tech products, Malaysia can boost its competitiveness even in the face of tariffs.

“Therefore, it is crucial for the government to support local technology companies with grants and incentives to accelerate investment in development of proprietary Malaysian IP such as IC design and advanced technology equipment,” he stresses.

Additionally, Malaysia must diversify its markets by exploring new opportunities in Europe, Asia and emerging economies. Participating in free trade agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership will create alternative export channels for the semiconductor industry, says Chuah.

He opines that Malaysia could reduce its reliance on the US markets by leveraging its BRICS partnership, aligning with technology-driven nations, and strengthening its position in global semiconductor supply chains.

“This approach would help mitigate US tariffs and create new growth and collaboration opportunities within BRICS,” he adds.

High tariffs will be disastrous

QES Group Bhd co-founder and managing director Chew Ne Weng observes that BRICS will potentially welcome a few new members from the region, including Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia.

“All these Asean nations will focus more on neutrality and trading instead of going into an anti-West stance. Malaysia has stated clearly, we want to be independent and stay neutral in the geopolitical tensions between the US and China.

“With the looming Trump 2.0 coming into power in the next few weeks, I don’t think Malaysia’s semiconductor sector will be his priority target. After all, most of the American and European multinational corporations’ (MNCs) back-end plants are in Malaysia,” he explains.

Chew says imposing high tariffs on these MNCs will be disastrous for the whole ecosystem of test assembly plants around the Southeast Asian region. Therefore, he believes Trump will not act irrationally against the chip sector.

He says Malaysia should continue to aggressively attract semiconductor companies from the US, Europe, Japan and South Korea to expand their operations or invest in the country, by offering attractive incentives, transparent and stable policy, as well as a good pipeline of talent. “Against this backdrop, Trump 2.0 will be risking global isolation if the semiconductor segment in Malaysia is still being targeted by the US for imposing high tariffs.”

Chew predicts that Malaysia will continue to be in a comfortable position for the next three years, if the government stays neutral and “not offending the US too much” in terms of policies on business and foreign affairs.

He reiterates that unlike the solar panel makers, heavy tariffs are unlikely to be imposed on semiconductor manufacturers around the Asean region as they originate from either the US, Europe, Japan or South Korea, with just a handful from China.

“Most of the solar panel manufacturers located in Asean originated from China. The tariffs imposed are targeting China solar panels manufacturers,” Chew observes.

Is Trump bluffing?

TT Vision Holdings Bhd co-founder, CEO and executive director Goon Koon Yin recognises the potential impact of possible US tariffs on the BRICS nations, as it could introduce a new layer of complexity that would hinder the industry player’s business operations and near-term performance.

However, given Malaysia’s significant involvement within the global semiconductor supply chain, coupled with the country’s long-standing partnerships with the US-based firms, he believes this will offer some form of insulation from direct fallout.

“The key challenge will depend on how we are able to maintain this balance, leveraging our relationships with both the US and BRICS nations without being overly reliant on one another. Trump’s claim of imposing tariffs on BRICS is more likely a negotiation posture and we see low likelihood of implementation,” Goon remarks.

Nevertheless, he agrees that the imposition of anti-dumping duties on solar products from Malaysia and other Southeast Asian countries could signal an increasing willingness by the US to scrutinise other industries, including semiconductors.

Goon is of the view that Malaysia could adopt a multi-pronged approach to protect the semiconductor industry from the potential fallout of US tariff implementation. This could include diplomatic engagement, which would require Malaysia to advocate its role as a reliable and neutral partner in the semiconductor supply chain.

Furthermore, the government could also implement certain initiatives to promote enhanced collaboration between the MNCs to further deepen their footprint in Malaysia, which could also help protect the industry from any sudden trade disruptions.

He points out that the narrative of the US-China trade war is evolving. Initially, Malaysia emerged as a key beneficiary of the trade tensions, attracting investments amid diversifying global supply chains.

But with the US’ increasing scrutiny on Southeast Asia as seen with its anti-dumping duties, Malaysia’s semiconductor sector faces growing challenges.

“Malaysia’s ability to maintain neutrality while navigating its BRICS affiliation will prove to be the key in determining the nation’s future trajectory,” says Goon.

As for TT Vision, he says, the group sees the evolving market dynamic as an active opportunity to capitalise on its strategic position within the value chain by fostering stronger relations with companies within the BRICS bloc, particularly those in China and India which may want to mitigate their risks by increasing reliance on Malaysia.

‘Malaysia will continue to be beneficiary’

UWC Bhd deputy group CEO Dr Matin Ng Chin Liang says Malaysia’s “partner country” status in BRICS enables the country to prioritise trading decisions that best serve the nation’s economic interests, while avoiding unnecessary alignment with geopolitical blocs.

“Malaysia’s recent application to join BRICS may have implications for the economic and strategic positioning, particularly in relation to its semiconductor industry’s role in global supply chains.

“Greater engagement with BRICS could offer potential opportunities for market diversification, technological collaboration and trade ties, but any changes in tariffs or trade policies would need to be assessed carefully,” he warns.

Ng adds that Malaysia’s ability to manage its relationships within BRICS alongside existing global partnerships will play a role in ensuring the semiconductor industry remains competitive and integrated within the global supply chain. “Malaysia’s strategic importance in the global semiconductor supply chain, supported by the presence of multiple industry-leading MNCs, minimises the risk of significant exposure to potential US tariffs.

“Unlike countries perceived as direct threats to US interests, such as China — which faces additional tariffs of 10% — or Mexico and Canada with proposed tariffs of up to 20%, Malaysia occupies a crucial supporting role in the supply chain. This positioning ensures Malaysia is viewed as a collaborative and essential partner rather than a competitor.”

Taking these factors into consideration, Ng believes Malaysia’s semiconductor industry will continue to benefit from trade tensions in the coming years. “The tariffs on Chinese exports may redirect US import demand towards other countries, including Malaysia. This trend mirrors what occurred during the initial phase of the trade war in 2020 when Malaysia’s exports to the US rose by 2.4% year on year to RM46.15 billion.

“If the trade war intensifies in the future, we anticipate a similar upward trend in Malaysia’s trade performance, positioning the country as a continued beneficiary of these global shifts in supply chains.”

TA Securities research manager and tech analyst Tony Chan Mun Chun concurs that Malaysia is likely to experience a net positive impact from trade diversion and relocation.

“Although the possibility is there, I think the chance is slim that tariffs will be imposed on the whole bloc. Instead of targeting BRICS as a bloc, I believe the focus will be on specific countries. For example, China and Russia will likely remain the main targets.

“At the end of the day, the US still needs someone to handle the back-end testing and packaging, and Malaysia remains a popular destination due to its political neutrality and well-established ecosystem,” he says.

Chan also believes Malaysia should seek to diversify its export markets beyond the US by strengthening trade relations with other regions.

“One way for Malaysia is to have regular dialogue with US policymakers to gauge where the red line is, and make sure we don’t cross it,” he suggests.

Earlier this month, the US launched its third crackdown in three years on China’s semiconductor industry, restricting exports to 140 companies. The new rules target shipments of advanced memory chips and chip making tools to China.

According to Reuters, the restrictions include limits on shipments of high-bandwidth memory chips used in advanced technologies like artificial intelligence training, as well as new controls on 24 chip making tools, three software tools and equipment made in countries such as Singapore and Malaysia.

The crackdown affects nearly two dozen Chinese semiconductor firms, two investment companies and over 100 chip making tool manufacturers, which will be added to the US entity list. Companies on this list cannot receive shipments from US suppliers without special approval.

The new rules also expand US authority to block exports of chip making equipment from US, Japanese and Dutch manufacturers made outside these countries to certain chip plants in China. Equipment made in Israel, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan will be restricted under this rule, but Japan and the Netherlands will be exempt.

Following the announcement, Deputy Minister of Investment, Trade and Industry Liew Chin Tong had urged Chinese companies to refrain from using Malaysia as a base to “rebadge” products to avoid US tariffs.

More selective on FDI

Meanwhile, the domestic equity team at Nomura Asset Management Malaysia opines that over the near term, an intensified trade war between the US and China would trigger trade disruptions and a decline in regional trade flows.

“Historical experience from 2018/19 suggests that escalating trade tensions tend to lead to weaker global growth, given the impact on financial markets, consumer and business confidence.

“Similarly, Malaysia also witnessed slower economic growth over 2018/19, given its open economy. Heightened policy uncertainty could also weigh on investment decisions in the immediate term,” the firm says.

Given that Malaysia’s approved foreign direct investment (FDI) only started to see a meaningful step-up from 2021 onwards, Nomura believes the country should continue to benefit from supply chain shifts over the medium-term.

“While Malaysia has broadly benefited from supply chain diversification, plans by the US to broaden the tariff coverage to ‘Made by China’ from ‘Made in China’ could impact investment plans by Chinese firms,” it warns.

To prevent unnecessary scrutiny by the US, the Malaysian government could be more selective in approving FDIs, choosing those where there is genuine value-add proposition, says Nomura.

In addition, it says, the government can provide support to domestic companies to remain competitive despite potential tariffs via improved infrastructure, lower trade barriers, conducive policies and upskilling the labour force.

A key risk to the supply chain diversification narrative into Malaysia and the Southeast Asian region is that Asean is the fourth largest source of imports into the US after Mexico, Canada and China.

“Trump has already announced planned tariffs on Mexico, Canada and China. However, within Asean there is a great divergence between countries, with Vietnam seen as a more vulnerable target given the sharp widening of its bilateral trade surplus with the US since 2018,” says Nomura.

While Malaysia’s semiconductor sector remains resilient and poised for growth, industry players are cautious about the geopolitical complexities.

If Trump returns to power with his tough trade policies, and Malaysia’s ties with BRICS strengthen, the country will need to carefully balance taking advantage of opportunities while avoiding any punitive actions.

For now, industry leaders agree that Malaysia’s neutral stance and strategic importance in the global semiconductor supply chain remain its best defence.

But as geopolitical tensions rise and the US enforces stricter trade measures, Malaysia’s future in the global semiconductor industry will depend on its ability to adapt and handle diplomatic challenges effectively.

Source: The Edge Malaysia