Semiconductor boom – how long will it last?

06 Aug 2022

MALAYSIA or more specifically Penang has been a hotbed of semiconductor business since the 1970s, very early on winning the moniker of Asia’s Silicon Valley.

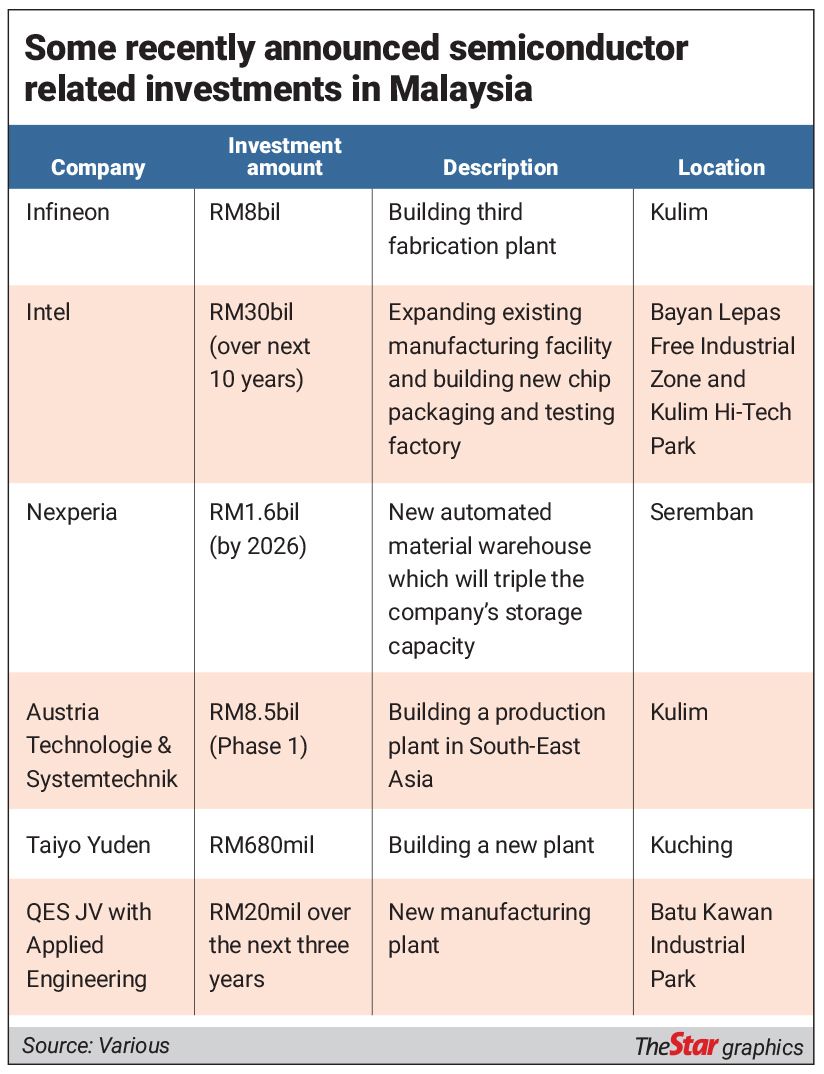

Fast forward to today, and the northern region of Malaysia is heating up with record levels of investments and re-investments pouring in, amounting in the billions of ringgit (see table).

But some interesting dynamics are taking place which could impact this semicon boomtown story for Malaysia.

For starters, with so much new production being built, is there a fear that the industry is heading into an oversupply situation?

This is more so, given the recession headwinds impacting the global economy.

Then there’s the new law passed by the United States government. Dubbed the Chips (Creating Helpful Initiatives to Produce Semiconductors for America) Act, the new law is aimed at drawing investment and production of semiconductors back to US shores.

Will this then lead to a slowdown of investments coming into countries like Malaysia?

And yet another hot topic that is likely to add to the semiconductor saga is the heating up of geopolitical risks related to Taiwan.

US House Speaker Nancy Patricia Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan has escalated tensions between Taiwan and China. Fears of reprisals from China could pose a critical problem to the global supply of chips as Taiwan is home to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the largest contract chipmaker in the world.

First, the potential oversupply situation. Not only are the multinational firms ramping up their semiconductor-related operations in Malaysia, but large local players are also doing the same.

For example, Unisem (M) Bhd, one of the largest assembly and testing players in the country, is building a new production facility in Gopeng at a cost of RM300mil, the first phase of which will be completed by next April.

Automated test equipment (ATE) manufacturer ViTrox Corp Bhd plans to invest between RM80mil and RM100mil in a new expansion project in Batu Kawan this year, adding 447,000 sq ft of floor space.

Globally also, there are as many as 10 wafer fabrication plants (fabs) being built. China has been racing to get a stronger foothold in semiconductors, throwing billions of dollars into the sector and building up capacity as quickly as they can.

Now more such operations are likely to get kickstarted in the US, considering the financial allocations given by the US government via the Chips Act.

Cyclical industry

The semiconductor industry is a notoriously cyclical one. Manufacturers are constantly pressured to come up with new technologies that create smaller transistors.

Additionally, fab construction and production boosts are slow and costly. Competition is ruthless. Companies risk losing out by the time their expansion plans are completed if their manufacturing know-how is behind their peers.

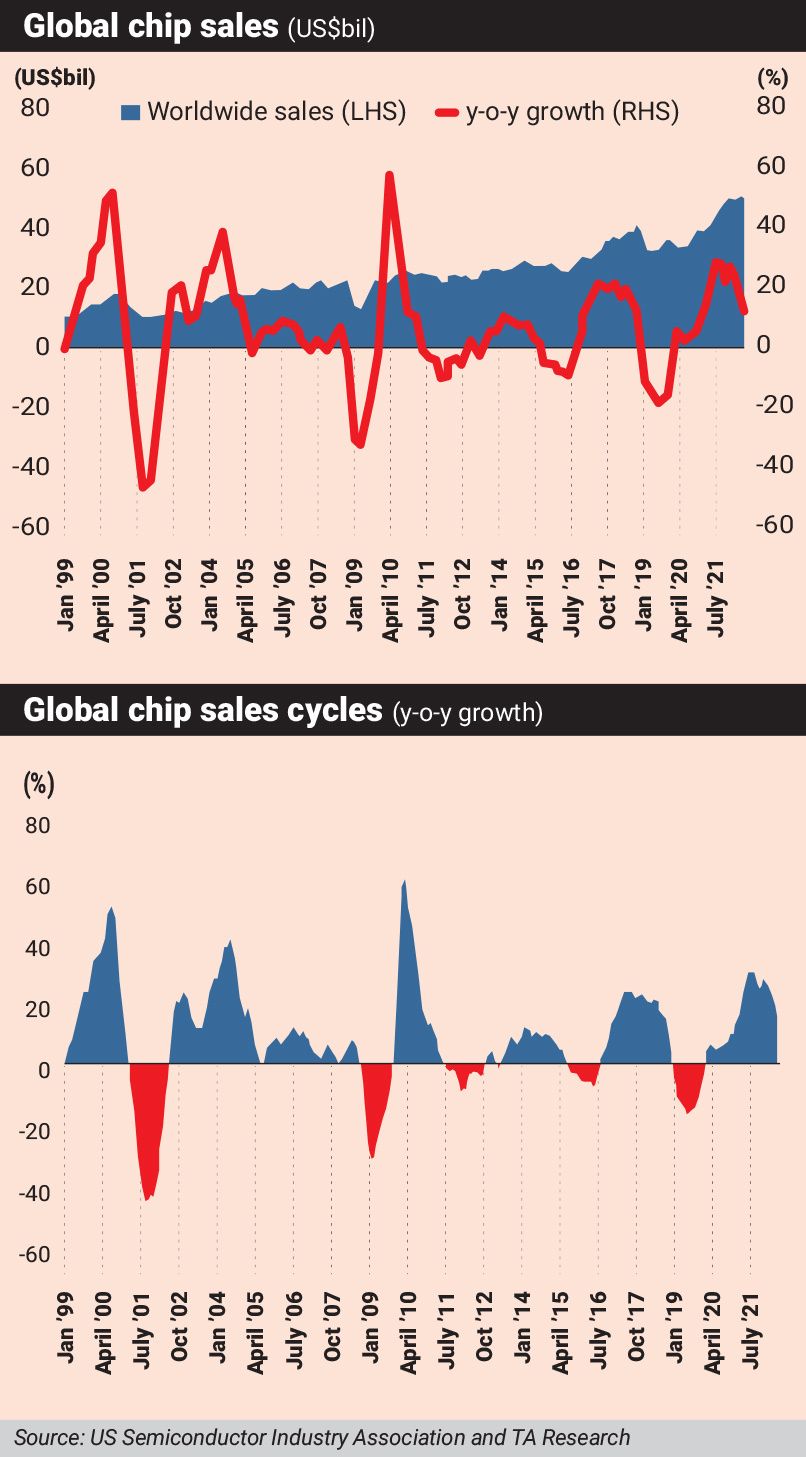

S&P Global Ratings pointed out this week that the global semiconductor cycle is heading for a downturn due to an ease in demand for consumer electronics. UOB Kay Hian Research, in a recent report, also projected global semiconductor sales to slow down in 2023 stemming from the expectation of a demand slowdown in the consumer electronics segment.

Deutsche Bank Research said in May that the current semiconductor cycle, which began in October 2019, has been running for 29 months, already above the historical average of 27.7 months.

But aren’t these exceptional times? It does seem so, at least going by one industry veteran’s view. Datuk Seri Wong Siew Hai, the president of the Malaysia Semiconductor Industry Association (MSIA), puts it like this: “There just seems to be no sign of a slowdown in the industry”.

Speaking to StarBizWeek via a Zoom interview, Wong adds, “So far the cyclical effect of the industry has not kicked in. The strong demand for chips has just persisted over the last two years.”

Wong notes that companies in the semiconductor ecosystem are going ahead with their expansion plans and that globally, there are 10 fabs being built this year and another 10 next year.

He notes the supply crunch of chips worldwide was brought on largely by the pandemic that accelerated the demand for chips in the consumer electronics and automotive industries.

“During the pandemic, many people were working from home so the sales of computers went up because they needed to set up their home offices.

“There was also a surge in gaming and eCommerce activities. Then there is the automotive industry that saw an increased number of people opting to buy cars instead of taking public transportation.

“All these activities need chips, not excluding medical devices as well,” Wong says.

He also explained that the situation was further exacerbated by fab closures in the US and Taiwan due to droughts, the interruption of chip manufacturing operations in Germany due to power outages and the implementation of lockdowns and movement control orders in some countries including Malaysia, which disrupted the production of semiconductors.

Wong, however, does not rule out a slowdown in the sector in the event of a full blown recession hitting countries across the globe or the outbreak of new wars.

Analysts say that despite the massive semiconductor supply coming into the market, demand has never been so strong because of new industries being created that need more and more chips.

These include sectors like automotive, computation and data storage, and wireless.

McKinsey in its report this year projected 70% of growth in the chip industry will be driven by the aforementioned three industries.

The automotive industry is singled out to be the strongest growing segment whereby the demand for chips could triple by the end of the decade.

Last week, MIDF Research pointed out that Singapore’s manufacturing output which grew at 13.8% year-on-year as at May 2022, was underpinned, by higher production of semiconductors. This in turn stemmed from strong demand from 5G markets and data centres, the report said.

Impact of US Chips Act

A significant development taking place in the global semiconductor space is the US passing the new Chips Act.

The law is aimed at helping the US regain its footing in chip manufacturing and becomes less dependent on foreign countries for crucial technologies.

Will it be a boon or bane for Malaysia’s semiconductor industry?

Chew Ne Weng, who runs QES Group Bhd, a niche Shah Alam-based ATE manufacturer, reckons it is a huge boon for Malaysia.

“The Chips Act is overall very good for the semiconductor industry, be it in the US, Taiwan, Japan as well as for players like us in South-East Asia.

Many companies in the ecosystem will enjoy the ‘waterfall effect’ of what the US will be doing. Malaysia is the main test and assembly packaging of integrated circuits for many US based multinationals such as Intel, Micron Technology Inc and Advanced Micro Devices Inc.”

MSIA’s Wong concurs. He explains that Malaysia and South-East Asia will become beneficiaries of the legislation as the Chips Act is focused on encouraging companies like Samsung, TSMC and Intel to build their leading edge manufacturing plants in the US and not so much for the “trailing edge” or back end part of the sector.

“We will benefit from the Chips Act because these corporations still need to outsource the packaging and testing services of semiconductors to other countries.

“As of now, Malaysia is not vying to attract wafer fabs into the country. We will only see the downsides of the Chips Act if Malaysia intends to do so,” he says.

In fact, Wong suggests that Malaysian-based semiconductor players ought to be seriously looking at expanding their capacity and eyeing to secure the expected new orders that will come from the US, stemming from the effects of the Chips Act.

“We have to expand our capacity of testing and assembly and other back end services to support the new volume of wafers coming out,” he says.

Geopolitics and semiconductors

Politics seem to be increasingly impacting the chip industry, one way or the other. For example, the recently passed Chips Act is their government’s move to ensure the country has the security of supply of chips for its industries.

And what the US is doing has already long been done by China. As pointed out recently by the New York Times, China’s drive to catch up and manufacture the most advanced chips is part of its “Made in China 2025” programme, an effort that began in 2015.

The US-based Semiconductor Industry Association, reckons that by 2030, China will have the largest stake in global semiconductor production, due to its government’s significant investments in this sector.

Meanwhile, tensions between China and Taiwan have escalated in recent days following Pelosi’s visit to the island.

At the height of her visit, the shares of TSMC took a hit. It has recovered some of those losses but still trades lower than what it did at the end of last month.

Meanwhile, TSMC’s chairman Mark Liu has told the media that if Taiwan were invaded by China, the chipmaker’s plant would not be able to operate because it relies on global supply chains.

Experts also believe that a China conflict with Taiwan would severely disrupt the global chip technology supply chain.

In an article by Fortune this week, an expert was quoted as saying that TSMC is the most irreplaceable company in the world today.

An economist was also quoted to say that Dutch firm ASML, which works closely with TSMC to produce advanced microchips, would likely move its key personnel out of Taiwan before any Chinese takeover.

Interestingly, ASML is one of the global top names in the semiconductor industry to have a presence in Malaysia.

Another big firm here is Lam Research, a leading US supplier of wafer fabrication equipment, which invested RM1bil for a new plant in Penang which opened last year.

Lam Research is listed on Nasdaq with a market capitalisation of US$71.54bil (RM319bil) and its presence in Penang has spurred on the local industry there.

Another biggie in Malaysia is Jabil Circuit Inc, a global provider of design, engineering manufacturing and supply chain solutions, which over the last few years has expanded its operations in the Batu Kawan Industrial Park.

This week, Malaysian Investment Development Authority’s (Mida) chief executive Datuk Arham Abdul Rahman praised Jabil Penang’s efforts in accelerating automation and digitalisation initiatives through its partnerships with local vendors in Malaysia.

Meanwhile, Wong points out how geopolitical tensions could work to Malaysia’s advantage.

“Because of the tension between the US and China, some of them have been looking at Malaysia as a so-called neutral place for investment,” he says.

He adds that many global companies seek to mitigate operational risks by building their factories in multiple regions. There is also a need to get closer to customers such as those already in Penang or Kulim, he says.

But with so many companies coming into Penang and existing ones ramping up production, is the infrastructure there stable enough to cater to this boomtime?

Available land for new plants in hot spots like Batu Kawan in Penang and the Kulim Hi-Tech Park in Kedah is hard to find and not to mention rising quickly in prices. Then there’s the concern of water and electricity, as these plants consume a lot of it.

Nevertheless, MSIA’s Wong opines that other than Penang which has issues with water availability, Malaysia on a whole has enough water to support the semiconductor ecosystem.

“The usage of water is rising because many factories are coming into Malaysia. However, Malaysia has sufficient water supply, it is just a matter of location.

“Penang is among the few states that has water supply issues, but this is not really concerning. Companies can choose to build their factories in other states like Kedah if Penang is unable to support the project. This is what is happening right now,” he says.

Wong notes the main crux of the problem is actually the shortage of workers at every level. Although there are no definite reasons as to why the majority of Malaysians choose not to work in factories, Wong speculates that it may be due to their preference for the gig economy which offers a more flexible working environment.

“When we talk about labour shortage in the chip industry, we are not referring to unskilled workers. In this sector, we need workers who have proper education, at least up to Form Five or Form Six in order to be able to be qualified to be trained as professional personnel in the factories,” he says.

Wong adds that Malaysia needs to employ talent from other countries as well to resolve the shortage of engineers in the industry.

“This shortage is also related to the number of students studying science and engineering in the country.

“The government should look into having programmes, like other countries are doing, that allow chip companies to hire students upon graduating to work for at least two years and the suitable candidates can be hired following that.”

Mida’s Arham concurs. He says the shortage of the right talent is a big hurdle for Mida to attract foreign direct investments.

“Although many big companies automate their production, they still require the right talents to run the machines and the production lines.

“Whenever Mida approaches foreign investors to invest in Malaysia, one of their main concerns is regarding the talent situation in our country,” he says.

One thing is for sure, the experts agreed regardless of geographical location or incentives, Malaysia has the potential to not only maintain its existing semiconductor ecosystem but expand it as well.

“Malaysia is very strategically located in Asean and can act as a base to cater to other markets in the region.

“We are also one of the countries in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership that includes about one third of the world’s population. All these factors give Malaysia the edge when it comes to attracting more foreign direct investments into the country,” says Arham.

Wong says that a strong ecosystem, business-friendly government as well as having the right talent to move the chip industry are the reasons for Malaysia being an attractive place for investments.

“This year MSIA is celebrating 50 years. This means we have 50 years of experience in the semiconductor industry. We have the contractors, technical consultants who know how to construct chip manufacturing factories.

We also have a business-friendly government with initiatives and task forces like the Express Construction Permit and Pemudah, that are committed to reduce red tape and facilitate investments,” he says.

Source: The Star